An English-Prussian bishopric was founded in Jerusalem in the year 1841. This alliance was the basis for the Protestants to settle in Jerusalem. Samuel Gobat, the second protestant bishop, purchased a compound on the Mount of Zion for the burials of relatives of both churches in the bishopric in the year 1848. In the year 1886 this alliance resigned because of the political general conditions. But it was decided to pursue the Cemetery together. For this purpose a committee of cemetery was founded 1906 which consisted an equal number of seats taken by the English and by the Germans. This committee owns still the administration of the Cemetery.

In the year 1917 a field for war graves for the German and Austrian soldiers which had been fallen in this area since 1916 was constructed. It was called the “nicht-konfessionelle Insel auf dem Prostestantenfriedhof” (“a non-confessional island on the protestant cemetery”).

After the Israeli war of Independence and the foundation of the state (1948–1967) the Cemetery was no longer useable for the churches which lay in the eastern part of Jerusalem, because the Cemetery laid directly west of the armed truce line between Israel and Jordan.

The Mount of Zion Cemetery is until today the one and only burial place of the German speaking protestant congregation in Jerusalem. Because of the everlasting right of ease in the Middle East the Cemetery possesses only a few unoccupied graves which are reserved for the resident Protestants.

Graves of Interesting People

Henri and Caroline Baldensperger (by Wolfgang Schmidt)

The roots of the Baldensperger family are in Switzerland, a few kilometers north of Zurich. The ancestor Felix Baldensperger left his homeland, Brütten, in the 17th century with his family. He belonged to the Anabaptists, who had their origins in the Reformation period and were exposed to persecution, forcing them to flee their homes. One part of the family settled in Baldenheim, Alsace, where Henri Baldensperger was born in 1823, the son of the saddler Johann Peter Baldensperger and his wife Barbara Gruber. In 1848 Henri, who was a turner by profession, left the rural environment of his family and embarked as a missionary to Palestine at the age of 25, sent by the Protestant Chrischona Mission near Basel.

The pietist Christian Friedrich Spittler founded this missionary work at the beginning of the 19th century. Among many other activities, he intended to establish an “apostolic way” that would take missionaries from Jerusalem to Ethiopia. As the first station on this route, a brothers’ house was founded near the Jaffa Gate, where Henri Baldensperger, together with the three other dispatched workers Conrad Schick, Ferdinand Palmer and Samuel Müller, lived. However, after a few months Henri Baldensperger went his own way.

There was a dispute with Spittler in Basel over the question of celibacy, which was imposed on the brothers of the Chrischona mission. Already from the time when he was in Alsace, Henri wished to marry his beloved, Caroline Marx. Caroline was from the Alsatian Niederbrunn, and served as a deaconess in the service of a pastor. She accepted his marriage proposal from Jerusalem, and made every effort to follow her future husband to Palestine as soon as possible. In the course of Baldensperger’s detachment from the Spittler brothers’ house, the village Artas, located a few kilometers south of Bethlehem, played an important role. The source area of the Solomon Pools had supplied Jerusalem with water for centuries and was considered the biblical garden of the Song of Solomon in the Old Testament for its lush vegetation. This was the time of the first European American agricultural colony under the English millenarian John Meshullam, who had converted from Judaism to the original Anglicanism. Millenarianism is an end-times belief based on the book of Revelation. Meshullam joined Baldensperger in October 1849 for one and a half years. The simple, close-to-nature life as a farmer and beekeeper family in Artas made him feel closer to God than to the Brothers’ House in Jerusalem.

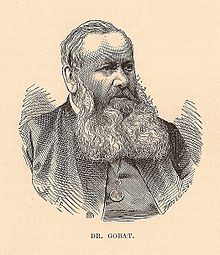

Soon, however, the living conditions for the young couple changed again. Samuel Gobat, second bishop of the Prussian-Anglican diocese in Jerusalem from the year 1841 (he is also buried at the Protestant Zionsfriedhof) hired Henri Baldensperger as head of administration for the school he founded on the Mount of Zion. This building continues to be the access to the Zion Cemetery till this day. But during the 18 months Henri lived in Artas, he had developed a feeling for the village that made it his home. The Baldensperger family spent all their weekends and holidays in Artas at that time, initially in the house that Henri had originally built in the valley, and later in a new house in the center of the village, which still stands today on the site of an old church from the time of the crusaders.

When Henri and Caroline finally retired after 45 years of service at the Gobat School, they settled in their home in Artas. But the following year, in January 1896, Henri Baldensperger died at the age of 73 years. His wife Caroline, who was not entitled to her husband’s pension, thanks to the financial support of her children, was able to spend the last 10 years until her death in the care of Artas. The last resting place for the 83-year-old was at the side of her husband in the Zion Cemetery.

On the very same spot there are also the graves of Charles Henri Baldensperger, one of her sons, died in 1905, and the grave of her daughter-in-law Elisabeth Baldensperger, who died at the age of 55 years. In total, Henri and Caroline had eight children. One of her sons died a few months after birth. Two sons died in France and one in East Africa, the others in Palestine. Descendants of Henri Baldensperger live today in France, Jordan and Canada.

For Philip Baldensperger, the death of his father sealed his spiritual heritage, as the excerpt from a letter he wrote on the occasion of his death shows:

“Full of confidence was your life and I hope that with

your body hope has not died, but

continues to be alive in all of us. Now I feel your

heritage. Hope is a solid bar and patience

a garment to go through from death and the grave

into eternity.”

* This text is based on the following article: Falestin Naili, “Henri Baldensperger : un missionnaire alsacien et le “vivre ensemble” en Palestine ottomane”. Article paru dans L’Annuaire de la Société d’Histoire de la Hardt et du Ried, no. 23, October 2011 (version d’auteur)

Literal quotations are marked in italics.

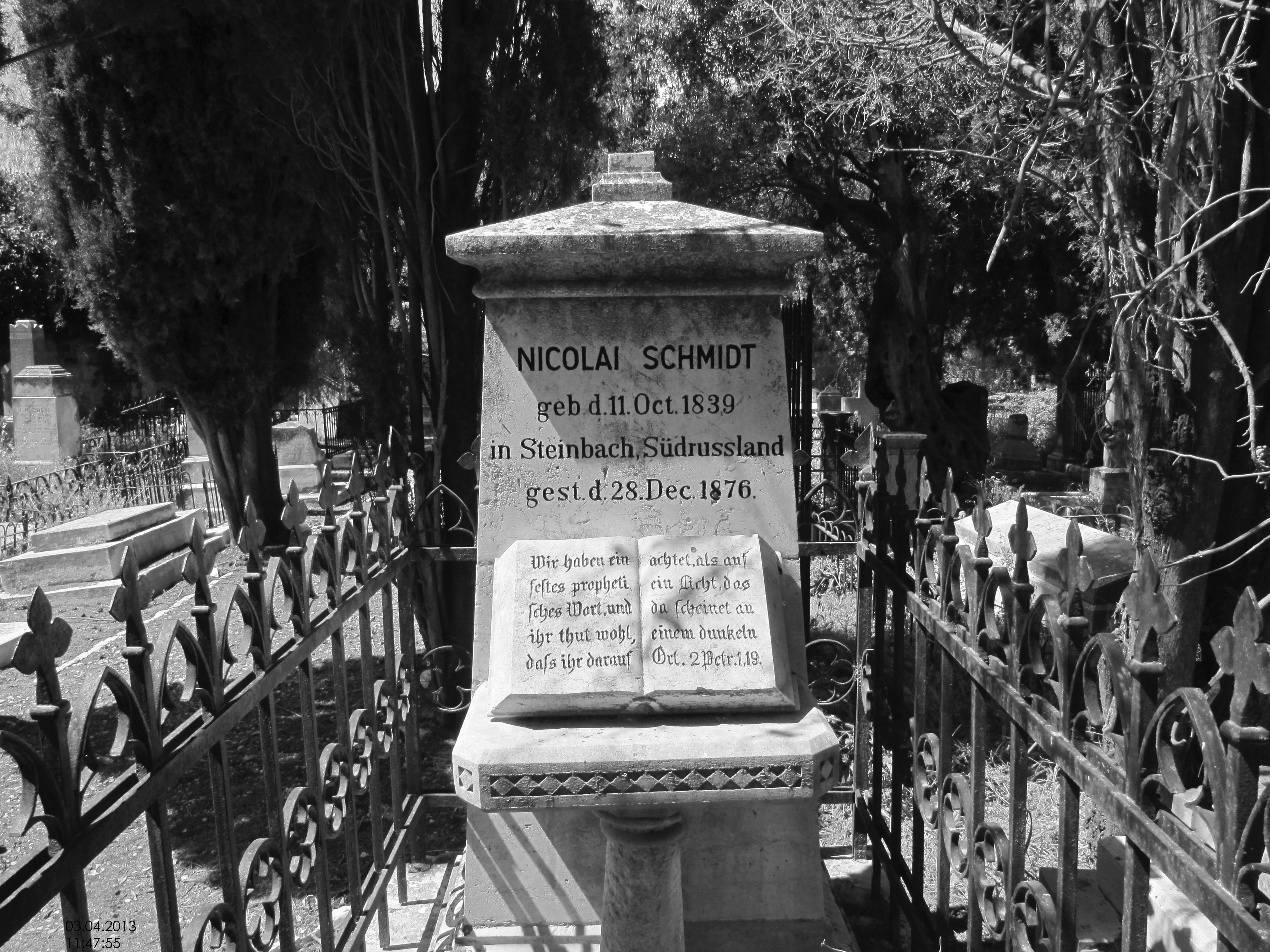

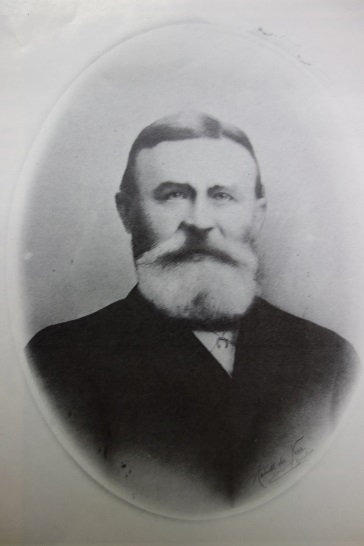

Nicolai Schmidt

Nicolai Schmidt (II), born on September 29, 1839 in Steinbach, Molotschna as the son of Nicolai Schmidt (I) and Katharina Matthies; died on December 28, 1876, father of Nicolai Schmidt (III), the last temple chief in Jerusalem. Important personalities are connected with the name Nicolai Schmidt in the movement of the Württemberg Templer. A look at the origins of the family leads from Jerusalem back to the northern edge of the Caucasus Mountains, then a thousand miles further back to the Molotschna in today’s Ukraine, from there back to the Vistula River near Gdansk and finally back to the Palatinate and Switzerland. Heinrich Schmidt (I), a Mennonite, had emigrated from the canton of Bern to Alsace around 1730.

His son Daniel and his family ran a larger farm near Zweibrücken in the Palatinate. His son Peter was just 20 years old when Napoleon’s great conquest began and all the young inhabitants of the occupied territories were drafted into his army. As Mennonites, the Schmidts refused the service with the weapon and so, given the circumstances, they had no choice but to flee from the conqueror. One night in the year 1809, they hastily left their farm and all their possessions. On foot they made their way to Galicia, where other Mennonites lived in the Lviv region. The following year they moved on to Russia, far to the south, to the river Molochna, which flows into the Sea of Azov near Melitopol. There Mennonites had already founded a few villages. The Russian Czarina Catherine II had invited German settlers to contribute to the development of this area, promising them free exercise of religion, preservation of native language, self-government, tax relief and exemption from military service. In the Gnadenfeld educational establishment of Peter Schmidt’s son Nicolai Schmidt (I), for the first time in the German colonies in southern Russia, the ideas of the “Jerusalemsfreunde” from Wuerttemberg found their feet. After several years this was followed by disagreements between the settlers, so that in 1863 covered by the temple thought some saw theirselves forced first to form their own community in Gnadenfeld and then later (1868) to move away from the Molotschna completely and to found an own colony in the Kaukasus foreland, “Tempelhof”. After the first temple colonies had come into being in Palestine, Nicolai Schmidt also thought of relocating there. In 1869 he visited Palestine and bought land in the Refaimebene, today’s Jerusalem district German Colony, with the aim to settle there. But on departure, he died unexpectedly on September 14, 1874 in Taganrog.

His son, Nicolai Schmidt (II) had already moved in 1872 from southern Russia to Jerusalem and began building a house. The laying of the foundation stone in 1873 for the house and mill in the “Emek Refaim” marked the beginning of a new Templar colony. A year later, his wife Anne gave birth to his first child, the daughter Rephaemie “Repha” Schmidt (1874). Nicolai tried to make a living by oil-pressing linseed and mustard. However, the Arab population did not win for it and preferred olive oil from the Arabian oil mills. Then first plantings of vines on the road to Bethlehem had success. Winemaking, production and distribution should become the professional goal of Nicolai. When his son Nicolai Schmidt (III) was born at the beginning of the year 1876, family happiness was combined with the professional success of the aspiring farmer. However, this luck was short-lived, because Nicolai Schmidt (II) died in December 1876 at just 37 years. He had to leave his wife Anna with two small children. Anna married three years after Nicolai Schmidt’s death in 1879 a Templar from near Stuttgart. Together they continued the wine business of Nicolai Schmidt. The Jerusalem wines were later exported to Germany and then traded especially in Stuttgart. His son Nicolai Schmidt (III) will be the last temple leader in Jerusalem (1941-1948) and with him the era of the Palestine communities will come to an end.

Nicolai Schmidt (II) was buried in 1876 in the Protestant Zion cemetery in Jerusalem. It took a strong sense of mission to take root in the heavy living conditions of Jerusalem in the late 19th century. This is attested to us in his gravestone inscription:

“We have a firm prophetic word,

and you do well that you pay attention

as a light,

that shines in a dark place.”

2 Petr 1,19.

The funeral of the earliest settled in the German colony settlers was still on the Zion cemetery, since the cemetery of the Templar colonists in Emek Refaim was created in 1878. Nicolai Schmidt (II) was the last of his family to be buried on the Prussian-Anglican Zion Cemetery.

After high school, Adalbert studied medicine in Vienna, and in 1872 became a Doctor of medicine. In that same year he graduated with a Master of Obstetrics. In 1874 he completed his training as a surgeon. After completing his military medical service, he committed to a two-year medical service with the Ottoman army in 1875, where he was stationed primarily in Nablus. However, this choice meant he had to give up Hungarian citizenship.

Dr. med. Adalbert Einsler

Dr. Adalbert Einsler was born on 24 May 1848 in Temesvar, which lay in the Hungarian part of the imperial and royal monarchy. Temesvar belongs to the Banat, which, like neighboring Transylvania, was populated mainly by German-speaking Danube Swabians. Today, the city belongs to Romania.

After high school, Adalbert studied medicine in Vienna, and in 1872 became a Doctor of medicine. In that same year he graduated with a Master of Obstetrics. In 1874 he completed his training as a surgeon. After completing his military medical service, he committed to a two-year medical service with the Ottoman army in 1875, where he was stationed primarily in Nablus. However, this choice meant he had to give up Hungarian citizenship.

After completing military service, Einsler worked for two years in the hospital in Tantur.

On May 15, 1879, he married Lydia Schick, the eldest daughter of the Württemberg government building officer Dr. h. c. Conrad Schick in Jerusalem. At that time, he converted from the Catholic to the Protestant church and assumed the Württemberg nationality.

From 1880 to 1884 he held the position of city doctor in Jerusalem, and was active in 1885 in Gaza, where he was employed as a microbiological expert in the control or containment of cholera medication. To emphasize the importance of this mission, one has to realize that there was no specific therapy for cholera at that time (neither vaccination nor antibiotics). In the same year he took over the medical management of the German-Israeli Biccur Cholim Hospital and the medical care of the leprosy asylum, “Jesus help”, of the Moravian Brethren. The sisters, who dedicated themselves to caring for the sick, came from Niesky.

The care of lepers was a special medical and scientific concern. He wrote a monograph “Observations on the leprosy in the Holy Land” (published in 1898, publishing house of the mission bookstore Herrnhut). At that time there was a great controversy as to whether the leprosy was of infectious or hereditary genesis. According to eyewitnesses (Otto Stahl, pastor in the Middle East and Swabia) he was of the opinion that it was impossible to decide the question of whether leprosy in Palestine was hereditary or contagious or both due to the data.

As is often the case with violent disputes, it turns out later that both sides are right. Leprosy is undoubtedly caused by Mycobacterium leprae, but less than 5% of people who have had contact with the pathogen also suffer from leprosy, which is mainly due to hygienic protective measures, but also to a genetic disposition. By the way, none of the sisters of asylum ever had leprosy.

In 1899, the German Emperor awarded him the Order of the Red Eagle, and in 1913 he was awarded the title of Medical Councilor by the King of Württemberg, and appointed by the Dutch Queen as Dutch Consul in Jerusalem.

Einsler died in Jerusalem in 1919 and was buried in Zion Cemetery.

Norbert Schwake honored his significant position in Jerusalem society and medical profession and highlighted it in several publications.

The Einsler family had 8 children, and sadly the family was not spared severe fatalities. The second-oldest son, Cony, was bitten by a rabid dog at the age of 9, and his father, a medical doctor, had to watch helplessly as his son died painfully from the disease. Today, it would be possible to cure the disease with a vaccine, but due to a lack of access to therapies, at least 60,000 people in Asia and Africa still die each year of animal-borne rabies. His son Friedrich, a lieutenant of reserve, was seriously injured in front of Reims in World War I and succumbed to his injuries in the hospital Rethel. He is remembered on a plaque in Zion Cemetery. All the other children except Walter, who remained in Jerusalem until his death, moved back to Germany, while the youngest daughter Gertrud married an American pastor (Tatley) and emigrated to the United States. There she wrote several articles about life in Jerusalem and the conventions and customs of the Arab population.

One may wonder why we should still be interested in the lives of our ancestors today. Although the individual stages of life are interesting enough, the attitudes and characteristics of the people at that time are particularly fascinating. At a time when today almost everyone strives for protection and self-optimization, the trust in God and the confidence of this generation are impressive. When emigrating or settling in Jerusalem, nobody had a pension, return ticket, or career guarantee, and yet people like Dr. Ing. h. c. Conrad Schick, Dr. Adalbert Einsler and his wife (to name but a few examples) accepted their duties with great confidence and trust in God. They believed in their mission even in difficult situations and made the best of the circumstances, but they also accepted the results without reservation. I think we could learn a lot from them today.

Ludwig Schoenecke

Ludwig Schoenecke is one of the more unknown people buried in the Zion Cemetery. Ludwig Schoenecke was born on January 26, 1847 in Hannover and died on November 28, 1902, about a year after his famous father-in-law Conrad Schick. Schoenecke came to Jerusalem at the age of about 20 as an employee of the Basel Pilgrim Mission. Christian Friedrich Spittler founded the pilgrim mission St. Chrischona in Basel in 1840. This should educate people to spread Christianity in distant lands, and to help alleviate distress and misery in these countries. Conrad Schick had come to Jerusalem in 1846 as a missionary, as well.

The pilgrim mission, in which Schoenecke worked, was, according to Spittler’s wishes, financially supported by the hoped-for profits. In the course of the dissolution of the not permanently profitable mission act Johannes Frutiger took over their banking division in 1872 and opened in early 1873, the bank J. Frutiger & Cie in a building at Jaffa Gate belonging to the Latin Patriarchate. These events are described in detail in the book by Hans Hermann Frutiger and Jakob Eisler “Johannes Frutiger – A Swiss Banker in Jerusalem”. There are further references to the professional life of Ludwig Schoenecke: Between 1872 and 1875 Schoenecke worked for a former employee of Spittler’s trading business in Philadelphia. He then returned to the Frutiger Bank in Jerusalem, edited debtor affairs and later worked as an authorized signatory at various stores of Frutiger Bank. In 1891 he signed the purchase contract for the Jewish housing estate Neve Schalom, where the corresponding site plan was created by his father-in-law Conrad Schick. Schoenecke was also active in publishing. His publisher let print Schicks guide through the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and there are postcards from this time with the imprint “Verlag L. Schoenecke” on it.

In Jerusalem, Schoenecke came into contact with the German-speaking colony and its members. There was sociability, club life, especially singing clubs, joint excursions, church walks, regular lectures and musical evenings and Schoenecke also got to know the couple Schick and his three daughters. He especially liked their middle daughter Frieda, who was 13 years younger than he. So it happened that on November 14, 1878, he married the 18-year-old Schick daughter Frieda. The wedding was certified by the German consul in Jerusalem Baron von Münchhausen. Schoenecke was warmly welcomed into the Schick family, to which soon the Einsler family (the Schick daughter Lydia had married the doctor Dr. Adalbert Einsler, leader of the “Leper Jesus-Asylum” of the Moravian Church), belonged. There were regular meetings at Schick’s house on Sunday afternoon and a hearty family life. Ludwig and Frieda Schoenecke had a total of seven children, six daughters and a son.

Visits to Germany were rare, but especially for medical treatments one drove home. Schoeneckes arrived in Germany in the summer of 1887 with four children and an Arab nurse in order to have Frieda undergo medical treatment in Berlin. The son Ludwig, born in 1884, was sent to the school in Höxter and later began to study medicine. He died in the First World War in 1915 at a lung penetration in Russian-occupied Poland and was buried there. A brother-in-law wrote that the grieving mother bore the death of her son in pious resignation and “brought this sacrifice, albeit with a bleeding heart, to the Fatherland”. The daughter Hilda, born in 1895, came via Kaiserswerth to Germany, studied medicine as one of the first women, in Halle and Hamburg, and finally came in 1924 to the North Sea island of Amrum. Here she was active as a family doctor and should also clarify whether the former feudal hotel and spa “Zur Satteldüne” was suitable as a children’s rest home. “Miss Doctor”, as she was commonly known on the island, came to a positive assessment, organized the construction of the child rest home, and became its leader until she retired in 1960, honored with the Federal Cross of Merit. Her sister Martha Schoenecke worked in the X-ray department of the children’s home. Almost all other Schoenecke daughters, mostly unmarried, moved to Amrum; they settled in the village of Nebel and died there.

One wonders how the young woman Hilda Schoenecke, who grew up in Jerusalem, could feel comfortable on a rough North Sea island. But Jerusalem and Amrum, in spite of all climatic, political and other contrasts, have something in common: a harsh landscape, a barren flora and a lot of sand. And: Amrum sometimes has beautiful summers “with a wealth of light over dunes and Kniepsand as I only knew it at home in Jerusalem.” Thus, Hilda Schoenecke wrote in her review of the suitability of the hotel as a children’s rest home.

All Schoeneckes were very religious and felt connected to Jerusalem for life. For the baptism of a niece Ludwig Schoenecke 1885 Jordan water sent from Jerusalem to Altdöbern in the Lower Lusatia. The bottle arrived safely. Ludwig Schoenecke died early after a short illness at the age of 55 years. The inscription on his tombstone reads: “Christ is my life and dying is my gain (Phil 1,21).”

BillionGraves is the world′s largest resource for searchable GPS cemetery data. For more information about the graves located in the Protestant Cemetery click the link below. The website offers GPS data and pictures of graves as well as a search function. For full access you will have to register or log in with Facebook.