Nirit Shalev Kalifa

Outside the Old City walls, close to the Zion Gate, stand the 14th century St. Saviour church and the adjacent Armenian civil cemetery. The church courtyard, surrounded by an arcade, has served as a burial ground for the Armenian Patriarchs of Jerusalem since the 18th century. The bishops, guardians of the holy sites and second in rank to the patriarchs, are buried under the paving in the center of the courtyard. In charge of the holy sites and the church’s treasures, these men had great power when they were alive. Now, in death, the stones set on their graves serve as pavement for pilgrims and visitors to step on, a testimony to the bishops’ humility.

In the years after the First World War, following the Armenian Genocide, many Armenian refugees arrived in Jerusalem and settled within the grounds of St. James monastery. The Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem allocated a large area of the Mount Zion cemetery to civilians, meaning those who were not members of the clergy. The allocated land has since been divided to an area meant for church use, where monks live and priests are buried, and to an area intended for non-clergy burial.

Between 1948 and 1967 the cemetery was in no-man’s land between Israel and Jordan, and many buildings, tombs and ornaments were damaged. Residents of the Armenian quarter received a temporary burial area within the monastery compound inside the Old City, which was under Jordanian control. After 1967 Old City residents were once again able to use the Mount Zion cemetery. The second floor of the church building was renovated, and the arches were closed with glass windows. In the 1970s the Armenian community began construction on a new church, intending to incorporate old tombstones in the church walls. However, as a result of planning issues and the new Mount Zion zoning plan, construction stopped and the foundation was left to crumble.

The civil cemetery is still used for burial today, but due to significant emigration in the late 20th century with many Armenian families leaving Jerusalem, the cemetery is now mostly abandoned.

The church compound is also the place of residence for priests and other members of the clergy serving in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The church and the courtyard, which were neglected for many years, have recently undergone restoration during the tenure of current Patriarch Nourhan Manougian.

Ceramic Decoration in the Courtyard and the Altar

The altar, located on the eastern wall, in the alcove closest to the church, was decorated in 1928 by the founder of Jerusalem’s Armenian ceramics tradition – David Ohanessian. The blue tile on the altar’s side panel reads:

David Ohanessian, man of Kütahya, who in 1919 founded the ceramic arts in Jerusalem, created these tiles in his workshop to cover the altar in honor of his parents and all his loved ones who have passed away. 1928, under the Patriarch Yeghishe Tourian

Another panel close to the altar, which has not been confirmed as Ohanessian’s work, covers the entire wall and features an Armenian cross in its center. Prof. Nurith Kenaan-Kedar described the panel:

The blue tiles, decorated with a black pattern, create a unified surface on which the giant cross appears, surrounded by a white frame over the background, as a singular image and a sign of revelation.

Other panels featuring giant Armenian crosses were produced during the 1920s and 1930s in the Palestine Pottery Workshop, owned by the Balian and Karkashian families.

Setrak Balian’s Grave

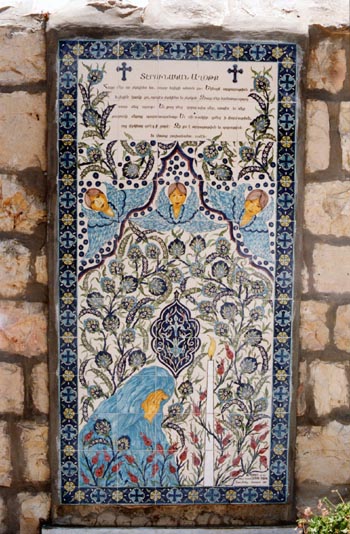

The work of Armenian ceramic artist Marie Balian is featured on the grave of her husband Setrak, who passed away in 1997. Setrak, a potter, was the son of Neshan Balian, a prominent figure in the early days of Armenian ceramics in Jerusalem. The tombstone set in the cemetery wall shows Balian’s signature style. The Grieving figure represents the artist; the three angles represent the couple’s three children. At the bottom of the panel, red tulips with broken stems and lowered crowns represent sorrow and mourning.

The Monument

An obelisk at the heart of the cemetery is a monument and the resting place of Armenian soldiers, members of the French-Armenian Legion, who died in the battle of Arara in Samaria in 1918. Towards the end of WWI, members of Armenian communities from Turkey and other parts of the world volunteered to help bring down the reign of the crumbling Ottoman Empire. Twenty three Armenian soldiers lost their lives in the battle of Arara, under General Edmund Allenby’s command, and were initially buried in a mass grave near the battle site. In 1926, their remains were transferred to the Mount Zion cemetery and the obelisk was erected. As years passed, the monument became the central memorial site for victims of the Armenian Genocide, committed by Turkey in WWI.